Adirondack lakes, rivers getting saltier

By CRISTINE MEIXNER

Editor

PISECO -- The data shows road salt is causing great harm to Adirondack ecosystems.

That's according to Paul Smiths College School of Natural Resource Management & Ecology Interim

Dean Dan Kelting, who is also executive director of the college's Adirondack Watershed Institute.

Kelting spoke at the Dec. 9 meeting of the Adirondack Lakes Alliance at Piseco Common School. He

said he has been studying rising salinity levels for about seven years, and there is a grassroots effort to

raise awareness and change winter road management practices to protect lakes and drinking water.

"Invasive species and road salt are the two major quality issues for waters in the Adirondacks," Kelting

said. "We use a remarkable amount of salt on our roads, which is having significant impacts on our

aquatic systems and human health.

"These affects are cumulative; the longer we wait the more we will feel these affects."

Road salt is sodium chloride, the same material as common table salt. When dissolved in water it

separates into sodium and chloride ions.

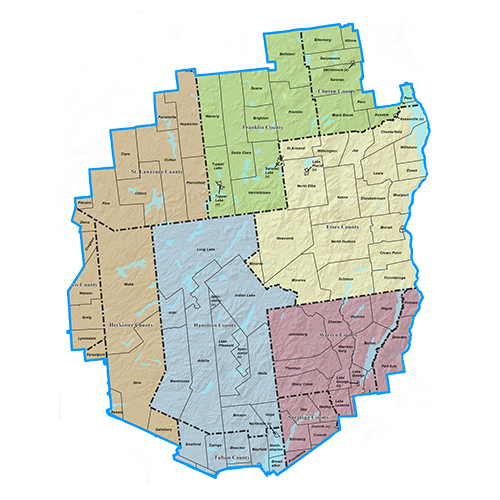

The Adirondack Park contains 2,831 lane miles of state roads and 7,725 lane miles of local roads,

Kelting said.

"State roads are treated with a yearly average of 108,000 tons of salt," Kelting said, "while local roads get 84,700 tons, so although state roads are only a third of the overall mileage they get a lot more salt.

"There is a lot of variation as to how [roads] are managed for snow and ice control."

In Fulton and Hamilton counties, he said, there are 450 state lane miles and 1,075 local lane miles using

17,170 tons on state roads and 11,800 tans on local roads, totaling over one million tons since 1980.

35 YEARS OF SALT

Widespread use of road salt started about 35 years ago in the Adirondacks, with the 1980 Winter

Olympics.

"About 6.5 million tons of salt have been imported into the Adirondacks and applied to our road network since 1980," Kelting said. "It is the most pollutant imported into the Adirondacks, twice that of acid rain."

Kelting says very little is known about the environmental effects of road salt.

"About half of it washes off into streams and lakes, about half percolates down through the soil, part is

held in the soil and the rest continues down into the groundwater," Kelting said.

A runoff model Kelting did showed 52 percent of stream length in the Adirondacks and 77 percent of the lakes show water chemistry changes due to road salt, he said.

"We have chloride data on 84 lakes and 25 streams from the Adirondack Watershed Institute and on 54

lakes from Adirondack Lakes Survey Corporation.

"We would like more monitoring volunteers," he added.

CONCENTRATIONS

Kelting said the median chloride ion concentration in lakes where there are no roads is 0.25 milligrams

per liter, and in lakes where there are roads it is 8 mg/l. Where there are streams and no roads it is also

0.25 mg/l, but streams near roads show 30 mg/l.

"Road density drives chloride density," he said. "As state road density increases salt density increases

when they are all treated the same for ice and snow control. As local road density increases it's a shotgun effect; there is no correlation due to variations in treatment."

Adirondack Watershed Institute had instruments measuring stream salinity at 30minute

intervals on four state roads for the past three winters.

"We found there are major peaks in the spring flush," Kelting said, "and peak concentrations of salt occur in the fall. As streams dry up they are fed by groundwater, so this is a major indication our groundwater is contaminated by salt."

This is a problem, he said, because it affects the food web.

"Algae can tolerate 500 to 1,000 mg/l, zooplankton can tolerate 530 mg/l, macroinvertebrates can

tolerate 2402,500 mg/l, and fish can tolerate 50230 mg/l."

The fish most affected, he said, will decrease in the fishery, and water clarity can be affected when there

are fewer zooplankton to eat algae.

WATER WELLS

A New York State Department of Environmental Conservation survey of 95 drinking water wells in the

Adirondacks shows sodium ranging from less than one mg/l to 273 mg/l and chlorine less than one mg/l to 393 mg/l.

Sixtyeight percent of the wells were contaminated by sodium and 75 percent by chlorine. "You can't

taste it at these levels," Kelting said, "but it can affect human health."

"We have been working with the NYS Department of Transportation so science can help inform

practices," Kelting continued. "DOT has been working with us to try to reduce the chlorine

concentrations in our water while still maintaining safe roads."

That may be true at the higher levels, resident John Casey said, but he saw DOT workers dumping road

salt at its shed on State Route 8 in Arietta, and had the photos to prove it. "The shed was overflowing andwhat was outside was not covered," he said. "It had run all over. It was like snow."

It took Arietta Supervisor Rick Wilt two attempts to get the salt cleaned up, Casey said.

Road salt is not going away any time soon. Sodium chloride is still the cheapest treatment for slick roads, and still the most popular choice, according to Kelting.

By CRISTINE MEIXNER

Editor

PISECO -- The data shows road salt is causing great harm to Adirondack ecosystems.

That's according to Paul Smiths College School of Natural Resource Management & Ecology Interim

Dean Dan Kelting, who is also executive director of the college's Adirondack Watershed Institute.

Kelting spoke at the Dec. 9 meeting of the Adirondack Lakes Alliance at Piseco Common School. He

said he has been studying rising salinity levels for about seven years, and there is a grassroots effort to

raise awareness and change winter road management practices to protect lakes and drinking water.

"Invasive species and road salt are the two major quality issues for waters in the Adirondacks," Kelting

said. "We use a remarkable amount of salt on our roads, which is having significant impacts on our

aquatic systems and human health.

"These affects are cumulative; the longer we wait the more we will feel these affects."

Road salt is sodium chloride, the same material as common table salt. When dissolved in water it

separates into sodium and chloride ions.

The Adirondack Park contains 2,831 lane miles of state roads and 7,725 lane miles of local roads,

Kelting said.

"State roads are treated with a yearly average of 108,000 tons of salt," Kelting said, "while local roads get 84,700 tons, so although state roads are only a third of the overall mileage they get a lot more salt.

"There is a lot of variation as to how [roads] are managed for snow and ice control."

In Fulton and Hamilton counties, he said, there are 450 state lane miles and 1,075 local lane miles using

17,170 tons on state roads and 11,800 tans on local roads, totaling over one million tons since 1980.

35 YEARS OF SALT

Widespread use of road salt started about 35 years ago in the Adirondacks, with the 1980 Winter

Olympics.

"About 6.5 million tons of salt have been imported into the Adirondacks and applied to our road network since 1980," Kelting said. "It is the most pollutant imported into the Adirondacks, twice that of acid rain."

Kelting says very little is known about the environmental effects of road salt.

"About half of it washes off into streams and lakes, about half percolates down through the soil, part is

held in the soil and the rest continues down into the groundwater," Kelting said.

A runoff model Kelting did showed 52 percent of stream length in the Adirondacks and 77 percent of the lakes show water chemistry changes due to road salt, he said.

"We have chloride data on 84 lakes and 25 streams from the Adirondack Watershed Institute and on 54

lakes from Adirondack Lakes Survey Corporation.

"We would like more monitoring volunteers," he added.

CONCENTRATIONS

Kelting said the median chloride ion concentration in lakes where there are no roads is 0.25 milligrams

per liter, and in lakes where there are roads it is 8 mg/l. Where there are streams and no roads it is also

0.25 mg/l, but streams near roads show 30 mg/l.

"Road density drives chloride density," he said. "As state road density increases salt density increases

when they are all treated the same for ice and snow control. As local road density increases it's a shotgun effect; there is no correlation due to variations in treatment."

Adirondack Watershed Institute had instruments measuring stream salinity at 30minute

intervals on four state roads for the past three winters.

"We found there are major peaks in the spring flush," Kelting said, "and peak concentrations of salt occur in the fall. As streams dry up they are fed by groundwater, so this is a major indication our groundwater is contaminated by salt."

This is a problem, he said, because it affects the food web.

"Algae can tolerate 500 to 1,000 mg/l, zooplankton can tolerate 530 mg/l, macroinvertebrates can

tolerate 2402,500 mg/l, and fish can tolerate 50230 mg/l."

The fish most affected, he said, will decrease in the fishery, and water clarity can be affected when there

are fewer zooplankton to eat algae.

WATER WELLS

A New York State Department of Environmental Conservation survey of 95 drinking water wells in the

Adirondacks shows sodium ranging from less than one mg/l to 273 mg/l and chlorine less than one mg/l to 393 mg/l.

Sixtyeight percent of the wells were contaminated by sodium and 75 percent by chlorine. "You can't

taste it at these levels," Kelting said, "but it can affect human health."

"We have been working with the NYS Department of Transportation so science can help inform

practices," Kelting continued. "DOT has been working with us to try to reduce the chlorine

concentrations in our water while still maintaining safe roads."

That may be true at the higher levels, resident John Casey said, but he saw DOT workers dumping road

salt at its shed on State Route 8 in Arietta, and had the photos to prove it. "The shed was overflowing andwhat was outside was not covered," he said. "It had run all over. It was like snow."

It took Arietta Supervisor Rick Wilt two attempts to get the salt cleaned up, Casey said.

Road salt is not going away any time soon. Sodium chloride is still the cheapest treatment for slick roads, and still the most popular choice, according to Kelting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed